Often, charismatic species are over-represented in scientific fields, more likely to raise funds, or considered ecologically more important than others. As a result, raising conservation advocacy, support, and awareness for megafauna species like elk, moose, bear, or wolves can be easier compared to rare, small, or uncharismatic creatures. Avians and mammals are some of the most studied taxa among the scientific community which could be due to several reasons. Some of these reasons include funding interests from agencies, societal preferences that influence and bias the choice of studied organisms, and remoteness, rarity, and observability of a species. With these biases in mind, how does a conservation scientist effectively communicate the ecological importance of protecting a certain species or habitat?

I suggest that using multiple frameworks and perspectives can be more appealing to people across multiple disciplines. For example, the intrinsic value of a mouse may appeal to a biocentric perspective, while the extrinsic value of a mouse may appeal to an anthropogenic perspective. Knowing your target audience and adjusting your framework of reason appropriately are key ways to gain support for species and habitat protection. For example, knowing that mice will most likely not be portrayed as the main attraction in the average nature documentary, I would lean toward using extrinsic value as the basis for the conservation of an uncharismatic species. How do you explain the extrinsic value of a mouse? My short answer is that several species of mice help provide our basic needs like clean water and air through soil and forest health. I will explain my reasoning with the following case study.

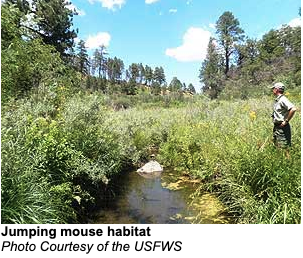

In 2014, the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse was listed under the Endangered Species Act after being extirpated from 70 – 80 percent of its historic range in the southeast United States. Livestock grazing, drought, wildfire, beaver removal, erosion, development, and climate change are all contributing factors that have degraded the riparian habitat that this species requires for survival. Why is this worrisome? Wildlife ecologist and nature columnist, Dr. Scott Shalaway once wrote, “Mice are keystone species in almost every ecosystem. In forests, fields, and deserts, mice represent food to predators of all sizes. They link plants and predators in every terrestrial ecosystem. Weasels, foxes, coyotes, hawks, owls, skunks, shrews, bobcats, and bears all eat mice.” Studies have shown that mice also play a huge role as seed dispersers, so much so that a mouse’s personality, whether it’s shy or bold when it comes to hiding and obtaining seeds, can influence the structure of an entire forest. Another study showed that mice help develop soils in restored sites by transporting soil mesofauna, like mites, which contribute to essential nutrient cycling. Studies like these, ones that look at mites on mice and observe their individual personalities, help illustrate how mice and other small, sometimes overlooked species, can play a big role in maintaining healthy soils and forest construction.

By protecting the habitat that mice live in, such as the riverine habitats and riparian buffer zones where the New Mexico meadow jumping mouse is found, we are preserving essential ecosystem services like erosion control, decreased sedimentation, and flooding and drought-resistance. These services create more resilient rivers and ecosystems which can help us combat increased severe climatic events like mega-fires, as well as provide clean water for surrounding communities, agriculture, and livestock. This argument that mice can help provide provisioning ecosystem services which in turn help us can be made for just about every abiotic and biotic component of an ecosystem. As effective communicators, we must explain the “why and how” behind the supporting science to conserve landscapes and protect species no matter how big or small.

Lauren Sadowski, Research Assistant|Lauren is a Master of Environmental Management candidate at the Yale School of the Environment specializing in Ecosystem Management & Conservation, and People, Equity & the Environment. Her past work and interests lie in human-wildlife conflict mitigation, anti-poaching, community development, and wildlife tracking and rehabilitation in southern Africa. She is interested in working at the interface of social science and ecology to develop equitable practices of community-based conservation and wildlife research in rural landscapes. Lauren holds a Bachelor of Science in Ecology, Conservation & Wildlife Biology from the University of Vermont. See what Lauren has been up to. | Blog