Black bear at a bird feeder

Carnivores have become social media sensations when they enter into urban areas. Hundreds of videos of bears breaking into houses and raiding the refrigerators or mountain lions lying under an unsuspecting resident’s back porch can be found with one quick online search. After a predator shows up in a suburban backyard, some might be delighted to be close to wildlife. But others might also be frightened for the safety of their children and pets. When an animal like a black bear becomes habituated to eating human food out of dumpsters, the story usually ends tragically with a wildlife agency forced to trap and euthanize the offending individual. Recently, it seems like this tale is becoming more and more common. But is it just a product of everyone having a smartphone and a story to tell? Or are carnivores actually coming into greater contact with humans?

“When things get weird…call Julie and Stewart” – Dr. Stewart Breck on urban carnivores

To find out more, I asked Dr. Julie Young and Dr. Stewart Breck, Research Wildlife Biologists at the USDA Animal Plant and Health Inspection Service (APHIS) National Wildlife Research Center (NWRC), to speak to us for the first Ucross Western Speaker Series event of 2019. Dr. Young’s research utilizes wild and captive carnivore populations to understand and reduce human-wildlife conflict. She leads the NWRC Predator Research Project and is also a Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Wildland Resources at Utah State University. Dr. Breck researches nonlethal methods for preventing conflict; the impact of carnivores on livestock; the influence of urban environments on carnivore ecology; and the population biology and behavioral ecology of carnivores.

Dr. Julie Young (left) and Dr. Stewart Breck (right)

On February 20, they both used the remote virtual platform Zoom to give their talk to Yale FES students without having to leave the West. Dr. Young’s research revealed that bobcats are living in highly urban environments like Dallas-Fort Worth, Texas. Although their elusive behavior makes them more difficult to see, camera traps show them active everywhere from railroad tracks to residential neighborhoods to parks. Bobcats are an example of a carnivore adapting its behavior to human environments in new ways. While they are not the subject of human-wildlife conflict as often as other species, they can be in danger of vehicle collisions when they attempt to disperse across roads. In order for animals to migrate out of isolated habitats in an urban matrix, wildlife corridors need to be established and maintained.

Bobcat walking through a culvert (Source: USGS)

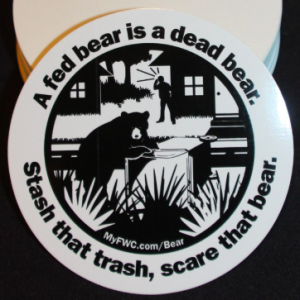

“A fed bear is a dead bear” – common mantra of wildlife managers

It turns out that for other carnivore species in urban environments, conflict with humans is indeed on the rise. Dr. Breck discussed his research on how a natural food shortage in 2012 led black bears near Durango, Colorado to enter urban areas in search of food, thus causing more bears to be killed by vehicle collisions and lethal removal. With the prospect of climate change, this situation can only get worse.

Sticker to remind the public to throw their trash in the proper bins to prevent attracting bears (Source: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission)

The good news is that there are some effective solutions to prevent bears from invading people’s homes. Dr. Breck provided a colorful description of his experiences working with two different cities in Colorado to implement these bear conflict prevention measures. One city he worked in was not willing to use the results of the research towards funding solutions or enforce them. But in Durango, city managers decided to invest $600,000 in bear-resistant trash containers and enforce local garbage ordinances. Conflicts with bears were shown to decline by 60% in areas that adopted the measures. And as an added bonus Dr. Breck has dubbed Durango “the Golden City of All Good Things, Inhabited by Caring Loving Smart People.” After hearing from Dr. Young and Dr. Breck, the students engaged them in a lively discussion.

Ucross Western Speaker Series Urbanization & Human-Wildlife Conflict event at Yale FES.

“Worth a Dam” – Heidi Perryman on beavers

A couple of weeks after talking to Dr. Young and Dr. Breck, UHPSI hosted a casual coffee chat on another source of human-wildlife conflict that often happens in urban environments: beavers. Sarah Koenigsberg, director of The Beaver Believers, joined us on March 5 along with Ben Goldfarb, Yale FES alum and author of Eager: The Surprising, Secret Lives of Beavers and Why They Matter. Both The Beaver Believers and Eager document how cities like Martinez, California want to remove beavers from urban streams because their dams can cause flooding. In Martinez, local resident-turned-activist Heidi Perryman started the group Worth a Dam to petition the city to permit the beavers to stay and instead install a water leveler device to prevent flooding. Ms. Perryman’s movement succeeded, and the beavers are now a popular attraction in town. Allowing beavers to naturally regulate stream flows can restore watersheds’ valuable ecosystem services throughout the West without a need for artificial infrastructure. This led us straight to the next Western Speaker Series topic: water in the west.

Coffee chat with Sarah Koenigsberg and Ben Goldfarb

“Less ecology and more sociology” – Dr. Stewart Breck on reducing human-wildlife conflict

Through these conversations with our fellow western wildlife enthusiasts, I learned that the problem of human-wildlife conflict is about more than just retaliation for a cow hunted by a mountain lion, a bear dumpster diving, or a stream blocked by a beaver. It’s about individuals’ different perspectives about the role of wildlife and nature in their lives. As development continues to expand in the West, people increasingly encounter wildlife, whether it’s a raccoon or a grizzly. The urban environment is a new frontier of the human-wildland interface. Because people today aren’t accustomed to encountering wildlife in a supposedly safe city landscape, the animals become a symbol for a threat to their well-being. At the same time, disagreement over who gets to make wildlife management decisions leads to the animals becoming the scapegoat (no pun intended) for a conflict between humans.

To reduce human-wildlife conflict, it will take a reframing of the situation and reconciliation of different viewpoints. Ultimately, everyone wants to live in a healthy environment. As Ms. Perryman said in The Beaver Believers, “I don’t want to divide it into environmentalists and non-environmentalists. I want to divide into people who drink water and people who don’t.” The ecological research is clear about the technical solutions, including wildlife corridors, proper garbage management, and reintroduction of beavers to watersheds. Some Western cities like Durango and Martinez were able to implement these strategies successfully. But lasting change will only come from a larger shift in our collective consciousness towards using our ecological tools to create better outcomes for both people and wildlife, rather than pitting one against the other.

—

Amy Zuckerwise, Symposium Coordinator | Amy Zuckerwise is a Master of Environmental Science candidate at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Amy studies carnivore ecology and conservation, with a focus in small and medium-sized wildcat species. Prior to Yale, Amy worked as a wildlife biologist in environmental consulting in Southern California. During her undergraduate degree at Stanford University, she majored in Biology with honors in Ecology and Evolution, and conducted her thesis research on the ecology of bobcats, pumas, and other mammals in northern California. See what Amy has been up to. | Blog