Over the last year, the rural gentrification research group has been approaching the subject of rural gentrification from a variety of perspectives. Rural gentrification has many, mutable meanings and definitions, both within academia and public discourse. Our research reflects this, as we have investigated the topic through a variety of avenues including changing land-use, environmental non-profit discourse, housing trends, and geospatial analysis.

Initially, I was curious about the spatial-temporal aspects of the housing crisis in communities experiencing rural gentrification. Specifically, I was interested in the ways the workforce is displaced from economic hubs and the ways in which this is amplified or facilitated through zoning and local level ordinances. Further, I was interested in the ways displacement from economic hubs affected the ability for the workforce to participate in the development or implementation of future workforce housing or policies to limit growth that promoted rural gentrification.

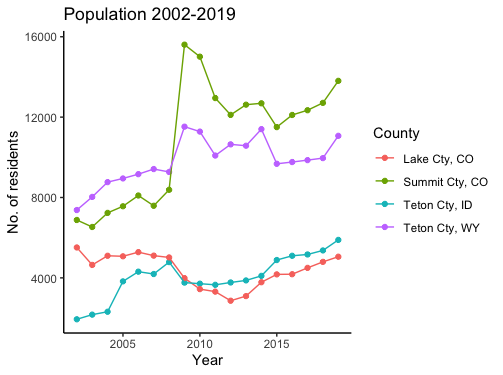

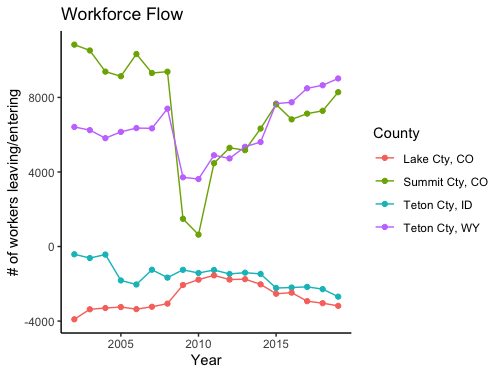

I explored these ideas in relation to two rural counties that serve as regional economic hubs: Teton, Wyoming (which includes Jackson), and Summit County, Colorado (home to Breckenridge, Frisco, Silverthorne, and Dillon). Parsing through various commuter and job metrics from the US Census, it became clear that Teton County, WY, and Summit County, CO both have nearby communities which serve in many capacities as workforce bedroom communities. For Teton County, WY, this is Teton County, ID, (home to Driggs and Victor). For Summit County, this is Lake County, CO (home to Leadville).

Conveniently, due to geography, these regions could be assessed at the county level. For example, the workforce that commutes to Teton County, WY, comes mostly from Teton County, ID. Similarly, much of the workforce that commutes to Summit County, CO comes from Lake County, CO. This allowed me to directly compare the same metrics (such as housing prices or population) across communities. As a researcher, this allowed me to see spatial-temporal trends via the changing socio-economic trends in economic hubs and their bedroom communities.

Despite this convenient way to compare communities across time and space, I found answering my research questions to be challenging. I came across housing needs assessments, capstone projects, scholarly articles, and even books that wrestled with these issues. These resources suggested that answering my questions would require more time, nuance, and specificity to a single region to answer comprehensively. Further, looking at many of the trends in the Teton County and Summit County regions, I noticed that many of the perceived local challenges were related to greater trends in political economy (such as the 2008 recession affecting population). This suggested that to truly grasp the issue of rural gentrification, one must consider larger systemic forces. Together, these observations were a bit overwhelming—worthy of deep and thorough study beyond my current timeframe and, frankly, the timeframe of many of those attempting to solve these issues on the ground.

However, I did notice one gap in many of the documents pertaining to housing and other concerns of community growth that I could address. Within all the quantitative data, there was a notable lack of qualitative data. There were many metrics of socio-economic trends, generated from the Census or other data services. However, understanding rural gentrification, and the housing crisis associated with it, also requires a question of values, of what it means to be a community, of change—questions not easily answered by survey generated data. In my assessment, some academics, journalists, and op-ed writers have attempted to bring forward these qualitative aspects. However, it is often in response to specific events, rather than long term trends or phenomenon. Or, in the case of academia, pertaining to a specific location and therefore of limited use for other locations.

Local people embedded in communities no doubt have a deep, intuitive cultural understanding of the issues associated with rural gentrification, such as housing. However, this personal understanding is hard to assess and difficult to report to others in a systematic manner. In response, I am compiling a report which includes a variety of metrics including workforce data, population growth, median housing costs, and cultural discourses. Specifically, I am using local newspaper archives—an accessible and consistent metric to measure cultural discourses. By searching keywords, such as “housing,” one can easily see the number of articles associated with that term.

Through my report, I hope to show how communities can assess qualitative indicators related to the housing crisis and rural gentrification in a manner that is accurate, useful, and efficient and systematically bridges the gap between quantitative and qualitative methods. And, in doing so, offer much needed method-driven cultural understandings to issues that are often communicated solely via data.

Mara MacDonell, Research Assistant | Mara MacDonell is a Masters of Environmental Science student interested in rural communities, science communication, transitioning economies, and environmental justice in the American West. While she grew up in rural, remote northern Minnesota, she fell in love with the West while working in social services policy and programming in Telluride, CO. She has also coached Nordic skiing, served as an AmeriCorps VISTA, and guided backcountry canoe and backpacking trips. She holds a BA in geology from Carleton College. In her free time, Mara enjoys backcountry skiing, running rivers, rock climbing, and painting. See what Mara has been up to. | Blog