During the first week of ranch crew, we all hopped in the van to visit a ranch not far from Sheridan College. Brian Mealor, a professor at the University of Wyoming and the director of the Sheridan Research and Extension Center, walked us out into the field and spent less than a minute searching the ground beneath his feet before he plucked a single blade of grass. He explained that it was Ventanata dubia, a plant that is climbing the ranks of invasive species that ranchers need to watch out for.

Me examining Medusahead Grass (Taeniatherum caputmedusae)

Ventanata was first found in Wyoming over two decades ago by the center that Brian directs and since then it has spread to around 70 acres around Sheridan. Ventanata is similar to cheatgrass in that it grows while native plants are dormant. Its early access to all the water and nutrients in the soil allows it to take hold of an area and spread. This is especially problematic since Ventanata has even less nutritional value than cheatgrass, potentially causing a serious issue for wildlife and farm animals.

There are over 300 rangeland weeds in the United States. Of those 300, there are a few that have a had a particularly large impact on the western United States, including cheatgrass, medusahead, and musk thistle. Controlling invasives is estimated to cost ranchers $5 billion annually and that is not including the effects of the plants on yield, interference with grazing, or livestock poisoning. Before ranch crew, I had never thought about the effect of invasive in rangelands. Now after seeing how prolific these species are, I realize what an important, complex, and seemingly insurmountable problem rangeland invasive species pose.

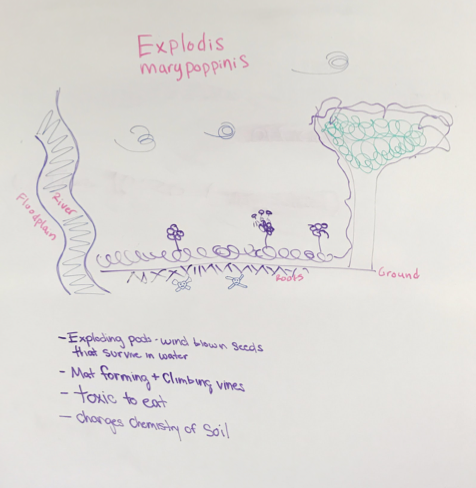

After we returned from the ranch visit, we gathered in a classroom in Sheridan College for a game. The goal of the game was to try and dream up the most destructive, biologically successful invasive species we could think of. Then, each team would come up with a management strategy to control the other team’s invasive plant. The most uncontrollable invasive would win. The only limitation given to us was that it had to be somewhat realistic. Each team stretched the idea of realistic with our absurd fictional plants. Traits included allelopathic compounds that were deadly to humans and animals, seeds that could survive in a seed bank for 100 years, and plants that could withstand flooding and fire. Because of the extreme nature of our plants, our management recommendations were also extreme. Each team settled on some variation of a “scorched earth” method to make a dent in our fake invasive nemesis.

A couple of our invasive plant creations.

The point of the whole exercise was to show us that while some of our inventions were not physically possible, our fictional plants were not that far off from what ranchers and resource professionals are having to deal with on the ground right now. The reason that certain invasives have become so widespread is that they have evolved an array of defenses and reproduction strategies that seem almost fictional in their ingenuity. This fact is made even more clear to me by the fact that I’m still finding cheatgrass seeds in my clothes a full 5 months after leaving Wyoming.

The game was useful in illustrating how difficult it can be to manage for these species. Once they are established there is often no perfect strategy and there are always difficult tradeoffs, like high costs or harmful chemicals. These considerations force to ranchers to ask themselves, when does it become not worth it to try to control an invasive but rather learn to live with a novel ecosystem?

Five months later, I am still struck by the complexity of invasive control and the impact invasives have on livelihoods and on ecosystems.