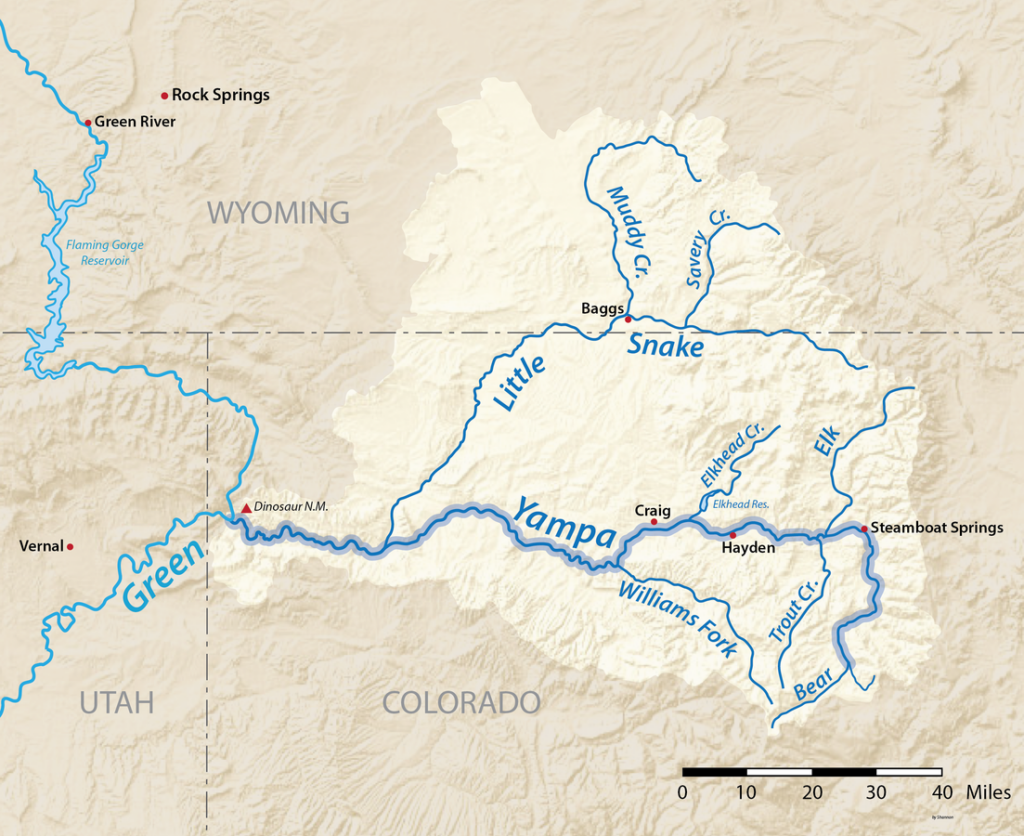

The life of the Yampa River has many important lessons, it remains the wildest tributary to the Colorado River system and makes up a significant share of the Upper Basin’s water flows. The Yampa River provides a 3rd of flows to the Green River, which is the largest tributary to the Colorado River. With the exception of a few reservoirs, the Yampa has survived thus far, undammed and in harmony with the people who depend on this water. Over the years, the many stewards and managers watching over the Yampa have beaten back large infrastructure projects to keep this river wild and free flowing. Climate change, the biggest anthropogenic threat of all, is causing snowpack to melt earlier, and adversely impacting base flows in this largely melt water fed river. As demand increases for the water provided by this dwindling resource, what does the future hold for the last wild river of Colorado? Can the Yampa continue to ebb and flow into the future, and still balance the needs of its people and the environment? You can read the full report here.

Image 1: Little Yampa Canyon on the Yampa River

(Source: Kent Vertrees from the Friends of the Yampa)

Image 2: Map showing the Yampa River and its tributaries

(Source: American Rivers)

The Role of National Parks Conservation Association

This summer I worked with the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA) to research the impacts of energy development, decline of coal power, and climate change on the Yampa River. Another aspect of this project was to better understand current water management practices and the role that NPCA can play in continuing to protect the Yampa River water.

It is common to hear about climate change problems manifesting in various ways for different communities, but the nuances of how these problems play a role in everyday implications is not always well understood. Working on this Yampa River project provided an opportunity to closely examine issues of water scarcity in the Western United States. The overarching goal of this research was to understand the role that natural resource management plays with everyday concerns of communities living in increasingly water scarce river basins. The Yampa River Basin embodies all the facets of a western waterway in distress. Focusing research on one small watershed in the west, rather than a multi-state region allowed me to better understand how climate change induced issues will continue to modify every small aspect of our lives.

The Yampa River is still a considerably healthy ecosystem, and the absence of large dams and reservoirs on it makes it stand out among all the other highly modified western river systems. In the past, Yampa River’s natural hydrograph has been enough to support its aquatic life, open floodplains, agriculture, municipal and industrial use, and a robust recreation industry. With Colorado being among the worst climate change hotspots in the country and the prospect of two degrees Fahrenheit of warming looming large, the Yampa River cannot continue as it has in the past. A combination of good fortune, and some active management has saved the Yampa River so far, continuing to save it for future generations will require innovation, collaboration, and bridging of political gaps. I started this project with the goal to understand what those integrative measures would look like, to fully grasp the meaning of collaborative management, the role of centering community voices, and how scientific knowledge can be a friend to policy making. Creating a water secure future for the west will require us to view water/air/land management issues as related to each other. Capacity building and funding sources are the big needs within the Yampa River Basin that NPCA can help address. With western coal plants shutting down soon, and hopefully an administration change in our future, right now is the time to take action.

The Birds Eye View of Yampa River Issues

The long running drought in the southwest will continue to worsen as temperatures rise, some climate scientists are calling it a “mega-drought” while others are seeing this as an increasing trend towards aridification of the region. The impacts of this drought are evident in the water systems of the state of Colorado and as a major tributary to the Colorado River, it is important to understand the implications of climate change on the Yampa River.

Demand for an increasingly scarce resource is increasing, and reservoir levels across the state are dropping drastically. Heat and low flow conditions are also stressing fish populations and a large number of fish kills are regularly being reported across the state. The human side of water scarcity is evident in the tagged and shut off water diversion for agricultural users as rivers, including the Yampa River are placed on call. Voluntary and mandatory closures across the state’s rivers are on an all time high. Water managers are working to find new ways of mitigating shortages; at the interstate, state, and town levels, balancing the competing water needs of various stakeholders, and often working with limited capacity and funding.

Add to this the overarching obligations of the state of Colorado to the system of Colorado River Basin. The prior appropriation system of water rights in the West means that Colorado may have to set aside its own water needs and deliver water to the lower basin whenever a compact call inevitably happens. With all of its intricacies and stakeholders, solving the water issues of the Colorado River with justice, equity, and environmental integrity might be amongst the most pressing challenges of the 21st century in the country.

The Yampa River is one piece in this big complicated puzzle, but one that is important to NPCA’s work for the protection or parks and park adjacent lands. The City of Steamboat Springs, located close to the Yampa River headwaters has already taken an active role in the management of this water and creating plans to mitigate shortages. The Stagecoach Reservoir and its managing entities have also partnered with local and national organizations to manage low flows and keep a minimum level of water flowing in the river during dry years. Additionally, two coal plants in the Yampa River Basin are shutting down in the next decade, the Hayden and Craig Power Plants hold relatively senior rights to a significant amount of water. This water made available by their closure is an important asset for many stakeholders, and provides a chance for environmental groups to secure instream flows for restoring river health. NPCA’s involvement will be crucial in securing future water rights for supplementing receding base flows and ensuring that Dinosaur National Monument located downstream to other users, continues to receive an adequate amount of water. The prospect of expanding this monument to National Park status also hinges on the availability of water. The importance of water conservation, and balancing developmental needs with environmental needs in the Yampa River Basin cannot be overstated.

Image 3: Tri State Generation Power Plant

(Source: Kent Vertrees from the Friends of the Yampa)

Climate Change and Water

The 2018 water year was the fifth driest year in the 123 year record of Colorado1. State averages of temperature are often not a good measure of individual basin level temperatures, but 2018, was a particularly warm and dry year for the Yampa River Basin as well.

Climate change induced rising temperatures have a threefold impact on the Yampa River;

- causes snowpack to melt earlier, disrupting the flow patterns, peak flows can occur much earlier in the season

- impacts aquatic species adapted to cold water environments, such as trout

- exacerbates drought conditions, higher evapotranspiration reduces the flow of water into the system

- causes a junior water rights holders to lose access to water as there isn’t enough discharge to meet everyone’s needs

A study by Milly and Dunne (2020) shows that Colorado River flows reduced on average by 9.3% per degree Celsius of warming. This is because of increased evapotranspiration, driven by high temperatures, snow loss and a consequent decrease in reflection of solar radiation. This research used the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) climate models and also looked at precipitation projections for the future. Even as warming temperatures are expected to increase precipitation, this rainfall will not be enough to cancel out the increase in soil moisture evaporation that is caused by high temperatures. Western Rivers in the future will run significantly lower than their historic levels.

Another analysis done by the Washington Post’s 2 Degrees Celsius Beyond the Limit series shows that western US, and specifically Colorado is amongst the worst climate hotspots, warming at a rate faster than other regions of the continent3. The Yampa River Basin fits squarely within the fastest warming region in the lower 48 states, and this hotspot has already warmed 2 degrees in the last century. According to some estimates the Colorado River has lost approximately 20% of its water in the last century.

In the absence of specific scientific studies on the Yampa River, one could extrapolate the results of Upper Colorado River Basin studies in the same region. Milly and Dunne predict 9-10% decrease in flows for every degree of warming. The Post analysis shows us a warming trend close to 2 degrees Celsius in this region. Hence, using extrapolation of the Upper Colorado River estimates, the Yampa River has lost 18-20% of its water over the last century due to climate change.

Another Upper Colorado River Basin study by McCabe et al (2017), shows that in the last three decades, flows in the Upper Colorado have reduced by an annual average of 7%, this is the largest mean reduction in runoff since record keeping began. Maximum reduction in flows was driven by the summer months of April through September suggesting that evaporating and snowmelt have a larger impact on diminishing runoff than precipitation (which is typically higher in colder months from October through March). As temperatures continue rising this summer season effect will become even more pronounced.

An empirical study by Woodhouse et al (2016) also links the increased frequency of warm years with diminishing flows in the upper basin rivers. Over the last two decades there has been a persistent drought in the west, which has negated any positive impacts that a handful of relatively wet years (2005, 2008, 2011, and to a lesser extent 2019) might have had on river flows.

The analysis by Woodhouse also sounds a warning note about the widely accepted hydrological flow prediction practices. Most water management practices use water year estimates (typically starting on October 1st) or the amount of precipitation during cooler months as a predictor of river flows. However, as these studies have indicated, summer month evaporation and high temperatures are significant drivers of evapotranspiration and diminishing flows. This suggests that the scientific community needs greater recognition of temperature driven reductions in river flows to accurately predict how much water may be lost in the upper basin as climate change worsens.

Image 4: The Yampa River looking east towards Hayden

(Source: Kent Vertrees from the Friends of the Yampa)

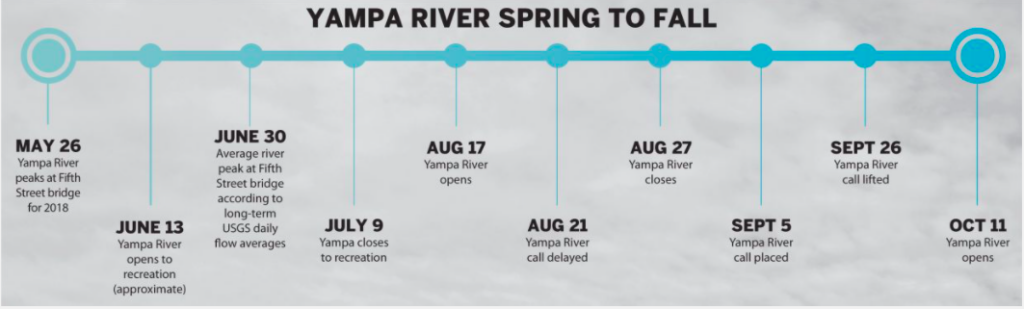

River on Call

In summer 2018, the Yampa River was placed on a call for the first time due to diminished flows caused by climate change. Being placed on call means that water uses on the Yampa river were curtailed. This primarily impacts holders of junior water rights, as those with senior water rights get their full allotment of water first. Closures on the river can be announced under three conditions: if the river reaches temperature 75 degrees F or above, stream flows fall below 85 cubic feet per second (cfs) or when the dissolved oxygen levels fall below a certain threshold. The previous water year (starting in September 2017) broke records on the Yampa River as temperatures were the highest ever recorded.

In June 2018, Colorado Parks and Wildlife closed a 0.6 mile stretch of the Yampa River at Stagecoach State park to fishing7. Critically low flow conditions caused by reduced precipitation and minimal snowpack caused this closure to stay in effect for months.

This closure was necessary because dry conditions and stressors of fishing can inflict immense pressure on fish populations, causing them to concentrate in residual pool habitats. Increased competition for food and decreased access to suitable habitat makes these fish easy prey for anglers and can cause rapid declines in population if not managed properly. As water temperatures rise up to 75 degrees F close to headwater areas, trout and other cold water adapted species are under threat. Trout function best in water temperatures from 50-60 degrees F, above 70 degrees F the fish often stops feeding and becomes susceptible to diseases5. Upper temperature tolerance limits for trout fall between 74-79 degrees F6.

The 2018 closure was eventually lifted due to an agreement between the Colorado Water Trust and UYWCD. After the agreement, a total of 600 acre-feet of water was released from Stagecoach Reservoir to increase downstream flows. Even with the additional flows, water levels observed in the river were more than 50% below the long term average flow for that time of the year8. In July 2018, the average river flow below stagecoach was approximately 90 cfs, whereas the long term average for that time period is 273 cfs.

The city of steamboat spring curtailed recreational uses of the river with a combination of mandatory and voluntary closures, the fishing, tubing, paddling season in 2018 only lasted about 40 days, one of the shortest in history9.

Image 5: The 2018 timeline for the Yampa River being placed on call

(source: Craig Daily Press)

Voluntary closures are often used as a tool by the local management bodies to protect the river, it’s a tool that has seen some success over the years. Education around the river, and other initiatives bringing public attention to these issues is vital for the success of the voluntary recreation closure model to work. However, voluntary and mandatory closures also have an adverse impact on the local economy. Recreation based business also lose income and employees have to be laid off when a critical revenue stream like the river becomes inaccessible

Implications of a Compact Call

The Yampa River being placed on call for the first time ever in 2018, also raised questions about the overall administration of water rights on the river, and the relationship of Yampa River to the Green and Colorado Rivers. The Yampa’s status as the biggest tributary to the Green River is important in this context because the Green River is the largest tributary to the Colorado River, and in whenever there is a compact call from the lower basin states, the upper basin (having junior water rights) must deliver the agreed upon water to the lower basin.

Yampa River being placed on call is one small piece in the larger picture of complicated water right holdings in the west. Approximately 52% of the water flowing into Lake Powell from the State of Colorado comes from the combined Yampa/Green/White River basins. The rules of the Colorado River Compact of 1922, also dictate that on a ten year timeline, Colorado must send a set amount of water to Lake Powell for use by Arizona, California, Nevada and portions of Utah and New Mexico. This allows Colorado for some flexibility to send less water in particularly dry years, but the deficit has to be made up in the following years.

When the Yampa River was placed on call in 2018, no precedent existed for cutting off users’ water supplies. The physical aspects of cutting off water rights involved the presence of measuring devices and proper headgates. Any users in the Yampa river without measuring devices were the first to lose their water, these were mostly agricultural users. Any users without formal court-decreed rights were also curtailed. Beyond these measures, the Division of Water Resources picked water uses with appropriated rights after September 16, 195110. If the river conditions hadn’t improved, this cutoff date had the potential of being moved to an earlier time, impacting even more users.

Water commissioners visited individual diversion sites for inspection. Non-compliance areas had their water shut off and tagged with a notice. During the 2018 episode, the city of Steamboat springs also lost some of its water rights, fortunately this was a small proportion of the overall water used by the city. Steamboat Springs augmented its supply by purchasing additional water rights from the Stagecoach Reservoir.

The water rights held by Craig and Hayden Power Stations were older than many of the agricultural and municipal users, and these facilities were in no danger of having their water cut off in 201810. The water situation in the Yampa River would have to get a lot worse before the consumptive use of coal fired power plants is curtailed.

Some Next Steps

Climate Change is the biggest threat to the Yampa River currently. The booming Front Range economy is getting increasingly dangerous for the river basin as water development projects for suburban populations on the other side of the Continental Divide create uncertainty. With these background threats in mind, the Yampa River is currently tackling the issue of low base flows, and coming to terms with the reality that in the future not all water rights holders on the river will get their share of water.

The phase out of coal power plants and shifts to renewable energy has created an avenue for conserving large amounts of water, and this shift in the energy portfolio has the potential to serve as a catalyst for innovative water management strategies. Moving from an extractive economy to a recreation based economy will be important for the Yampa River basin in the future. This will create more green jobs as coal based jobs get phased out, and is an opportunity to realign the next generation of residents in the river basin with goals of environmental protection. Building community partnerships should be at the forefront of all efforts to insightfully solve climate change problems in the Yampa River. Connections with local organizations working on the ground are an important first step, because the best conservation happens with community support.

The recommendations within the full report are focused on the role NPCA can play in these conversations and where there is an opportunity to build more partnerships, contribute capacity, and promote the vision of healthier water systems. NPCA’s work is focused on park and park adjacent lands, because the Yampa River ultimately flows into the Dinosaur National Monument, these upstream issues need to be resolved for the continued protection of priceless natural vistas.

Image 6: Echo Park, at the confluence of the Yampa and Green Rivers

(Source: National Park Service)

Humna Sharif, Research Assistant and Western Resources Fellow |Humna Sharif is a Master of Environmental Management Candidate at the Yale School of the Environment and is focusing on Water Resource Science & Management, and Environmental Policy Analysis during her time at Yale. She is interested in exploring the interconnectedness of freshwater systems with land, and how we can address issues of water quantity/quality through ecosystems management practices, and policy changes. As a Western Resources Fellow, Humna is working with the National Park Conservation Association (NPCA), and Sustainable Waters on issues of water and land conservation in the Western US. She holds a BA in Environmental Sciences, and Environmental Thought & Practice from the University of Virginia and worked at the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) in Washington D.C prior to beginning her graduate work. See what Humna has been up to. | Blog