Two students from the Yale School of the Environment’s Ucross High Plains Stewardship Initiative teamed up with The Nature Conservancy in Wyoming to deepen the culture of conservation in these iconic grasslands.

Figure 1: Grassbanks may offer exceptional opportunities to deepen conservation in ranching landscapes by integrating social, ecological and economic considerations.

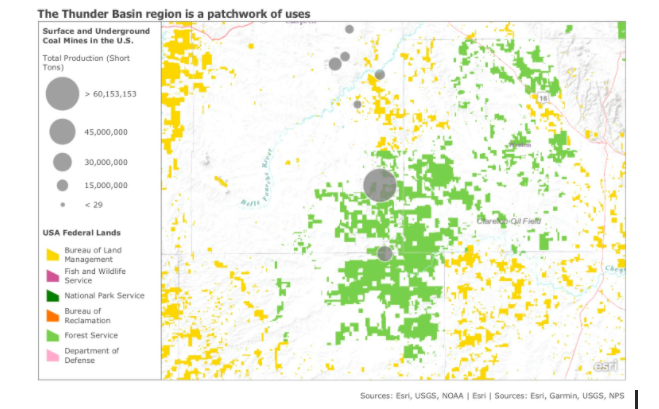

With over 13.2 million acres, the grasslands of Thunder Basin, Wyoming are part of a patchwork of federal, state, and private land that represents the biggest expanse of contiguous grassland in the continent (Figure 2). The homeland of the Crow, Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux, these lands have seen their fair share of degradation from the Dust Bowl to climate change and oil and gas drilling. So, we teamed up with The Nature Conservancy in Wyoming (TNC Wyoming) to explore new strategies to deepen grassland conservation efforts in this region of the state. TNC Wyoming, along with many other nonprofits, community groups, businesses and agencies in the region have been working on collaborative conservation strategies to protect critical grassland habitat for decades.

Figure 2: With over 13.2 million acres, the grasslands of Thunder Basin, Wyoming are part of a patchwork of federal, state, and private land that represents the biggest expanse of contiguous grassland in the continent.

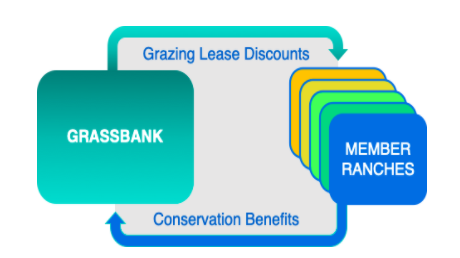

Figure 3: Grassbanking is a conservation approach that provides forage in exchange for conservation benefits and promotes collaboration among ranchers and conservationists. Grassbanks involve both land where alternative forage is available, the grassbank, and also the land where conservation benefit occurs, the management area.

Now, TNC Wyoming is exploring a new approach called grassbanking – a conservation strategy that is both a physical place as well as a collaborative approach to ranching and grassland conservation. A grassbank is ranchland where forage is offered at a discounted rate to local ranchers who elect to do conservation practices on their deeded property, or “home ranch”. The ranchers’ deeded property is the management area where conservation benefit occurs. (Figure 3) Grassbanks are a voluntary, market-based mechanism that gives participating ranchers immediate returns for taking actions on their deeded lands which result in tangible ecosystem benefits. In addition, this strategy can strengthen social ties between conservationists, regulators, and ranchers, encouraging the development of new win-win strategy that can be put into practice locally right away (Figure 4).

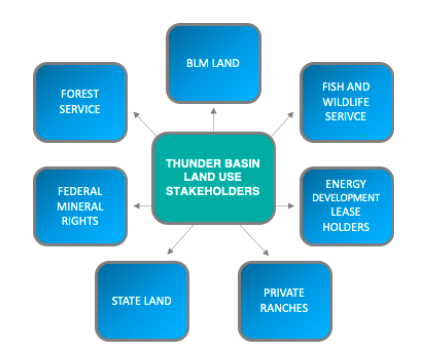

Figure 4: Grassbanks can strengthen communication and social ties between stakeholders including conservationists, regulators, and ranchers, encouraging the development of new win-win strategies that can be put into practice locally right away.

Grassbanks have been used to protect endangered species such as the greater sage-grouse, prairie dogs, and various bird species. They can encourage new ranching or management practices like wildlife-friendly fencing or development of a ranch management plan. In addition, by providing ranchers with stable forage which they can use to support ranch income, they can help prevent practices like “sodbusting”, which converts native grasslands to row crops like wheat or corn. These conservation actions improve management on both the grassbank itself as well as on the ranchers’ deeded land. These projects also have the potential to benefit local ranchers by offering forage at a discounted rate. This allows ranchers and their businesses to be resilient through seasonal and climatic variations. In addition, access to forage is important for families who are increasingly supporting multiple generations on the same land, offering young or beginning ranchers a chance to build their herd while maintaining healthy stocking rates on their home ranch.

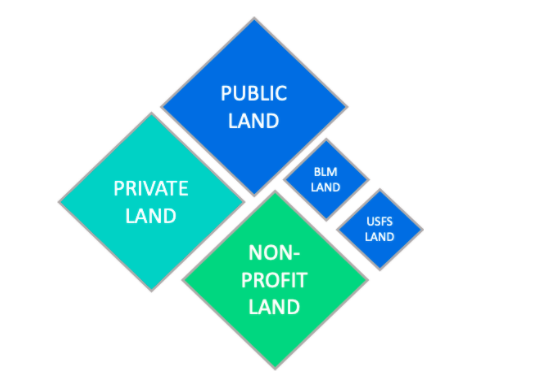

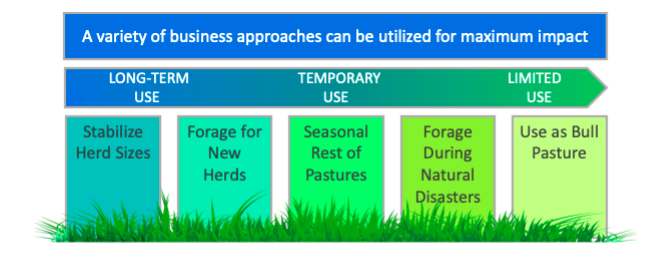

While studying the potential to develop a grassbanking program in the Thunder Basin region of Wyoming, we learned that grassbanks may offer exceptional opportunities to deepen conservation in ranching landscapes by integrating social, ecological and economic considerations. However, these programs are also challenging to develop and depend on having significant community buy-in. A grassbank may require tens of thousands of acres, which if purchased on the open market would equate to tens of millions of dollars. However, this cost could be moderated by developing a mixed-ownership approach in partnership with other stakeholders (Figure 5). They also require a strong business model and we have identified several approaches that may be successful (Figure 6). In addition, these projects require ongoing, and potentially permanent, support from a supporting entity like a nonprofit organization, necessitating a long-term approach from the partners involved.

Figure 5: A grassbank may require tens of thousands of acres of land which, if purchased on the open market, would equate to tens of millions of dollars. However, this cost could be moderated by developing a mixed-ownership approach in partnership with other stakeholders.

In our research, we highlighted several ways that a nonprofit like TNC Wyoming could improve their likelihood of success. First, we developed a rubric that would help program managers select a property that would give them the greatest chance of success (Figure 7). Next, we highlighted the critical aspect of social buy-in from the surrounding community. Local ranchers, regulators, and conservationists hold deep knowledge about the region and collaborating closely from the start is likely to yield far better outcomes. We also highlighted several areas for further research such as benchmarking existing grassbanks, performing economic modeling, and evaluating novel techniques that may lead to a stronger understanding of this concept if it were to be put into practice.

Figure 6: Grassbanks require a strong business model to ensure long-term success. This figure identifies several approaches that may be successful.

With the impact of COVID-19 looming large in some parts of the rural West, there is even greater need to consider how conservation programs can improve rural livelihoods. Grassbanking represents a powerful way to strengthen relationships between conservation interests and rural needs – a potentially powerful next step in our efforts to conserve this iconic landscape of the West.

Figure 7: This rubric can help program managers select a property that would give them the greatest chance of success.

For more information, please also visit the Thunder Basin Grassland Prairie Ecosystem Association’s website.

STUDENT RESEARCHER

Humna Sharif, Research Assistant and Western Resources Fellow Humna Sharif is a Master of Environmental Management Candidate at YSE and is focusing on Water Resource Science & Management, and Environmental Policy Analysis during her time at Yale. She is interested in exploring the interconnectedness of freshwater systems with land, and how we can address issues of water quantity/quality through ecosystems management practices, and policy changes. As a Western Resources Fellow, Humna is working with the National Park Conservation Association (NPCA), and Sustainable Waters on issues of water and land conservation in the Western US. She holds a BA in Environmental Sciences, and Environmental Thought & Practice from the University of Virginia and worked at the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) in Washington D.C prior to beginning her graduate work. See what Humna has been up to. | Blog

Katie Pofahl, Research Assistant and Land Management Field Practicum Participant | Katie is a Master of Environmental Management candidate at the Yale School of the Environment specializing in land conservation and business strategy. She grew up in America’s dairyland and learned the importance of working landscapes and sustainable rural livelihoods. Now focused on the wild and arid landscapes of the West, Katie works to create lasting conservation solutions for resilient landscapes and communities. She has restored habitat with farm-working families in the strawberry fields and ranches of California and she developed market-based incentives for fishing communities along the coast. At F&ES Katie works with the Center for Business and the Environment at Yale to educate land conservation practitioners about cutting-edge financial strategies. She also works with the Ucross High Plains Stewardship Initiative to assess best practices in grassland restoration for ranch lands in the Northern Great Plains. See what Katie has been up to. | Blog