At the end of the 20th century, scientists dissolved Ungulata. “Ungulata” was not a brand of dish soap or a chemical, rather, it was a taxonomic grouping that described “hoofed mammals.” Molecular evidence showed that elephants were only distantly related, and that whales were actually very closely related, to such animals as horses and cattle (1). It turns out hooves developed independently in at least two separate lineages: even-toad artiodactyls (like deer, cows, goats, and pigs) and odd-toed perissodactyls (like horses and rhinoceroses). And yet, “ungulate” is still a term used contemporarily as a heuristic or illustrative tool of the animals that belonged to the old grouping. Even though our understanding of how animals are related to each other may change, this does not change how animals are related to or interact with their environments (their ecology). Collectively, ungulates play many roles in their environments such

as:

- plant population control through herbivory (2)

- seed dispersal in their dung or on their fur (3)

- engineering habitats by wallowing and rolling around in dirt which stirs it up (4)

- engineering habitats by changing the stabilization and erosion regimes of riverbanks by selectively grazing certain riparian plants (5)

- engineering habitats by tramping down vegetation and trail building (6)

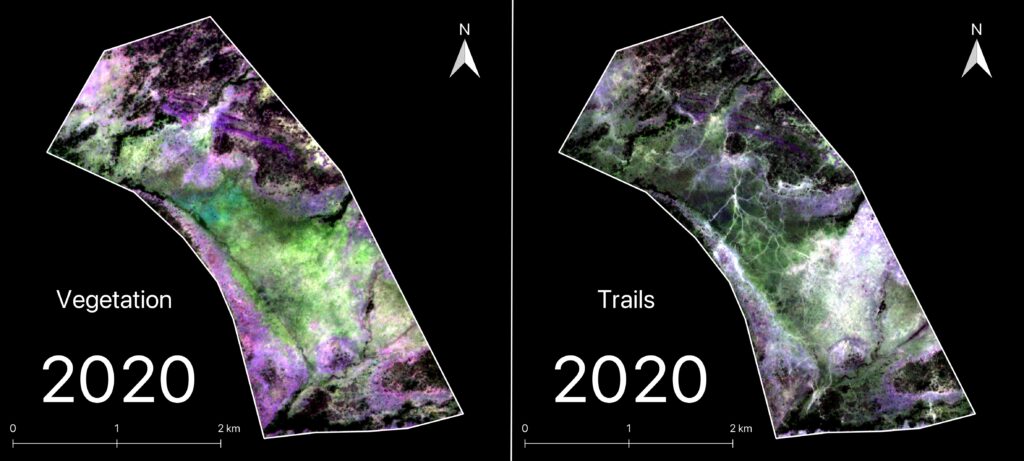

Last spring, I conducted a remote sensing project on the visibility of ungulate trails from space. I used imagery from the PlanetScope satellite constellation over the East African Serengeti of Tanzania from 2018-2023 for a series of analyses. After scouring the country, I found a 7 km² tract of land in which animal trails appeared like clockwork every May-June, and then disappeared by the end of every summer. The location and ephemerality of these trails corroborates the known migration route of herds of an ungulate, the Common wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), as they seasonally follow the best vegetation food sources in what has been dubbed “The Great Migration” (7, 8). What is notable about this pattern of animal movement is not just the sheer number of ungulates involved, but the fact that the traces of their movement and effects on the landscape are so wide-reaching that they are visible from space. However, even though “The Great Migration” may be one of the most publicized migrations of ungulates, it is certainly not the only one, and may not even be the greatest. In fact, we may not even need to leave the United States to find one that is comparable. The population of Common wildebeest numbers between 1 and 2 million individuals (9), but this also happens to be the population size of the American-native Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) in the American West (10), another migratory ungulate.

Of the 12 native, extant (living) ungulates in North America, pronghorn have the longest migrations (11). However, Pronghorn exhibit more than one type of migration strategy: seasonal migration, facultative winter migration, post-fawning migration, and many pronghorn do not even migrate at all (11). This diversity of movement patterns almost certainly contributes to a complex, dynamic landscape, and I would be interested to see if I could detect pronghorn trails in the American West as easily as those of African Serengeti ungulates.

One challenge inherent to trail identification at both locales is that without on-the-ground observations (“ground truthing”) it is very difficult to know which species created the trails, or if they were created by more than one species. In the Serengeti there are many other possible “trailblazing” ungulates including the Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), Zebra (Equus quagga), and Impala (Aepyceros melampus). In the United States, there are 11 other ungulate species besides pronghorn which include White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), Elk (Cervus canadensis), Moose (Alces americanus), Caribou (Rangifer tarandus), American bison (Bison bison), Bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), Dall sheep (Ovis dalli), Mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus), Muskox (Ovibos moschatus), and Collared peccary (Dicotyles tajacu) (12). In the end however, it may not even matter who makes the initial trail since so many species, both ungulates and non-ungulates use trails, and may eventually homogenize them. They are definitely important landscape features regardless.

By the way, speaking of trails, did you know that dogs can learn how to identify which direction a bicycle was traveling based on the tracks it leaves?

References

- Gheerbrant E, Filippo A, Schmitt A. 2016. Convergence of Afrotherian and

Laurasiatherian Ungulate-Like Mammals: First Morphological Evidence from the

Paleocene of Morocco. PLOS ONE. 11(7):e0157556. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157556. - Hobbs NT. 1996. Modification of Ecosystems by Ungulates. The Journal of Wildlife

Management. 60(4):695–713. doi:10.2307/3802368. - Albert A, Auffret AG, Cosyns E, Cousins SAO, D’hondt B, Eichberg C, Eycott AE,

Heinken T, Hoffmann M, Jaroszewicz B, et al. 2015. Seed dispersal by ungulates as an

ecological filter: a trait-based meta-analysis. Oikos. 124(9):1109–1120.

doi:10.1111/oik.02512. - Nickell Z, Varriano S, Plemmons E, Moran MD. 2018. Ecosystem engineering by bison

(Bison bison) wallowing increases arthropod community heterogeneity in space and time.

Ecosphere. 9(9):e02436. doi:10.1002/ecs2.2436. - Wolf EC, Cooper DJ, Hobbs NT. 2007. Hydrologic Regime and Herbivory Stabilize an

Alternative State in Yellowstone National Park. Ecological Applications.

17(6):1572–1587. doi:10.1890/06-2042.1. - Roundy BA, Winkel VK, Khalifa H, Matthias AD. 1992. Soil water availability and

temperature dynamics after one‐time heavy cattle trampling and land imprinting. Arid

Soil Research and Rehabilitation. 6(1):53–69. doi:10.1080/15324989209381296. - Dybas CL. 2022. Born to Roam: Tracking the Drama of Earth’s Ungulate Migrations.

BioScience. 72(12):1141–1148. doi:10.1093/biosci/biac096. - Holdo RM, Holt RD, Fryxell JM. 2009. Opposing Rainfall and Plant Nutritional

Gradients Best Explain the Wildebeest Migration in the Serengeti. The American

Naturalist. 173(4):431–445. doi:10.1086/597229. - Estes RD, East R. 2009. Status of the wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) in the wild

1967-2005. New York: Wildlife Conservation Society Working Paper 37. - Rickel B. 2005. Large native ungulates. Fort Collins, CO.

https://research.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/21181. - Jakes AF, Gates CC, DeCesare NJ, Jones PF, Goldberg JF, Kunkel KE, Hebblewhite M.

- Classifying the migration behaviors of pronghorn on their northern range. The

Journal of Wildlife Management. 82(6):1229–1242. doi:10.1002/jwmg.21485. - National Park Service. Bison Bellows: Why Manage Ungulates?

https://www.nps.gov/articles/bison-bellows-6-16-16.htm.

STUDENT RESEARCHER

Jeremy Pustilnik – Research Assistant | Jeremy Pustilnik is a Master of Environmental Science candidate at the Yale School of the Environment (YSE) where he works on the movement ecology and territorial dynamics of Argentinian owl monkeys. He received his B.S. in ecology and evolutionary biology from Cornell University where he worked on the predator-prey interactions between foxes and rabbits at groundhog burrows, the movement of stone martens across the Mediterranean, and the population ecology of salamanders. Prior to YSE, Jeremy worked on the tundra of the Arctic Circle with the USGS monitoring goose and shorebird nesting success and in the desert scrub of central Texas on the disease ecology of mice and metacommunity dynamics of soil arthropods. With Ucross and the National Wildlife Federation he is working in GIS to develop landscape models of pronghorn movement and the implications of wildlife fencing in the American West. In his free time, he enjoys flipping over rocks and logs to find snakes and bugs, flying his drone for service projects like mapping local parks, and reviewing scientific manuscripts for the journal Urban Naturalist, at which he is an editor. Blog