There are two things that are common knowledge if you live in a ski town (and you don’t have a trust fund to support you): 1) Getting a job is easy, which is good because you’ll probably need at least two; and 2) there is no housing.

Previous to matriculating at Yale, I lived in Telluride, CO for four years. Telluride is one of the many towns in the American West that is experiencing rural gentrification at some stage. Communities experiencing rural gentrification in the West are often those that are amenity or recreation-resource rich–the poster children for this phenomenon being Aspen, CO, and Jackson, WY.

Through my work at Ucross High Plains Stewardship Initiative at YSE, I’m working to better understand some of the challenges associated with rural gentrification in the West. Depending on your familiarity with these communities, it’s perhaps surprising to find out that these communities—often marketed as pristine getaways—have problems. But they do. And affordable housing is one of these problems.

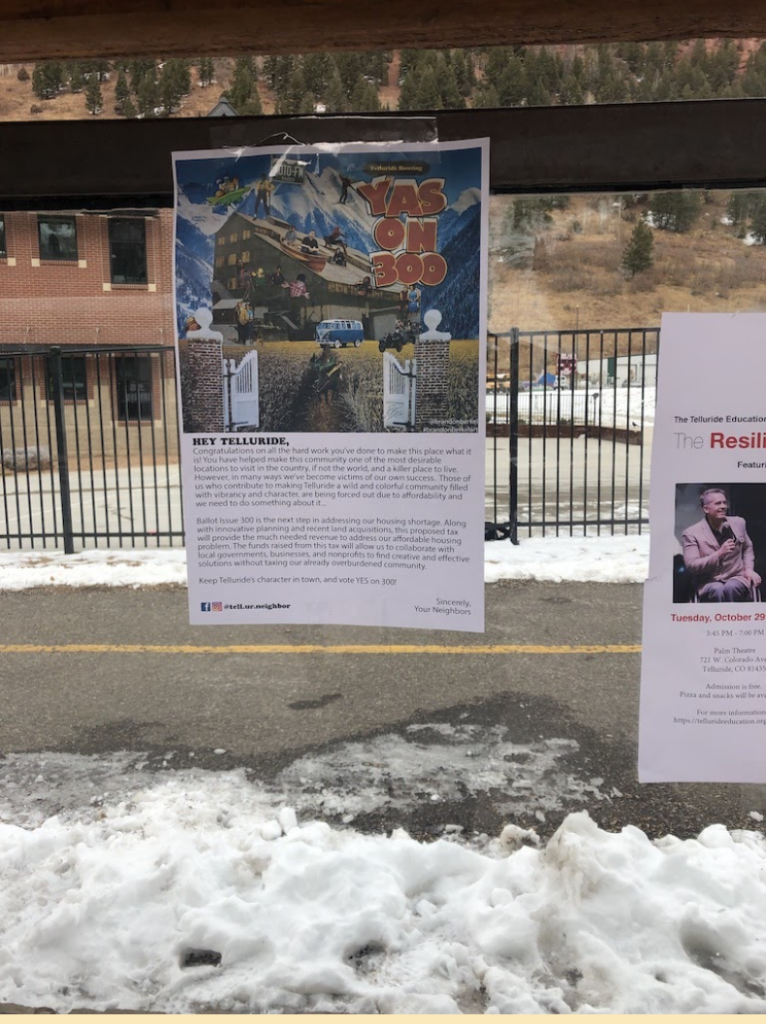

Poster encouraging voters to support an affordable housing initiative in Telluride

What is the affordable housing crisis?

Generally speaking, the affordable housing crisis in rural communities manifests in two ways. First, there is the actual financial cost of housing–what housing exists is expensive. According to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, if you pay 30% or more of your annual income on housing (rent or mortgage) you are considered “housing burdened.” While being housing burdened is hardly a rural or western phenomenon, recent research from Headwaters Economics finds that housing in recreation-dependent communities is less affordable than other places.

Second, there is limited availability of housing. Many of the rapidly gentrifying communities in the West are located in valley bottoms or abutting public lands (or both). Because of this, there is only so much land that can be developed and, ecologically, should be developed.

Furthermore, short term rentals (STR) have also become a significant part of the housing crisis in the West. While Vacation Rental By Owner (VRBO) was perhaps the first iteration of this (founded in 1995), the rise of Airbnb in 2008 created a financial opportunity where none really existed previously. With the ability to turn a property into a STR, people can invest in a property they perhaps wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford and use STR earning to pay off the mortgage. Other investors are drawn to STR as easy money makers; STR are currently lightly regulated, compared to traditional lodging options and offer owners a lot of flexibility on how to utilize the property.

The Covid pandemic, and the resulting “Zoom Boom”, has sped up the crisis as well. Now, in addition to competing with the easy money of STR, local workforce have to compete for housing with outside professionals who have flexibility and higher budgets moving to the area. Together this has created the conditions for a crisis.

Effects of the Crisis

The effects of the affordable housing crisis are myriad. However, perhaps most challenging to communities is the lack of housing for the local workforce. From servers and ski patrol to teachers and county administrators, finding appropriate housing can be nearly impossible in these communities. This limits the ability of the community to function, with businesses forced to reduce hours or even shut down due to lack of staff, high turnover, and a general degradation of community, as people move to regions and jobs that offer more stability. Furthermore, the challenges of the housing crisis are felt on an even greater scale by marginalized and at-risk communities including immigrants, children, and those in poverty.

Housing is a crucial social determinant of health. When people have unstable housing, it can have real consequences on mental health and overall well-being. I personally can remember the stress I felt paying nearly a thousand dollars a month to live in a room with tapestries for walls, no lease signed, and no keys to the apartment. When rumors that the apartment would be remodeled in the near future (ski town code for being transitioned from long term housing to a STR), I knew I had to get out of there. I got incredibly lucky and found a coveted place in affordable housing.

Sometimes you get lucky: the author’s million dollar view from affordable housing

Potential Solutions

Luck isn’t a solution, however, and the consequences of the affordable housing crisis are forcing communities to look for solutions.

Some communities, such as Summit County in Colorado, have been working on this issue for the last twenty plus years, building up the affordable stock, levying various taxes, and passing housing regulations. Others, such as Crested Butte, have just begun to invest. However, regardless of timeline, the challenges persist.

According to CPR News, in the recent 2021 elections, citizens in a dozen communities voted on ballot initiatives that offered a variety of policies to address the housing crisis. Many of the policies focused on limiting STRs. The effects of these policy solutions are yet to be determined, however, if history is any guide, they will hardly be sufficient.

As I continue my research on rural gentrification for Ucross High Plains Stewardship Initiative, I will explore topics related to affordable housing policy. Questions that drive my research forward include: Who is able to vote on initiatives regarding workforce housing? What is the influence of outside developers on local policy? Who benefits from increased affordable housing? Who benefits from the affordable housing crisis?

Understanding rural gentrification and its many associated challenges isn’t easy. As policy makers look for solutions, it’s crucial they consider the many factors influencing phenomena like the housing crisis and the fact that these factors don’t happen passively–they are the result of decisions made by policy makers and community members at a variety of levels.

Mara MacDonell, Research Assistant | Mara MacDonell is a Masters of Environmental Science student interested in rural communities, science communication, transitioning economies, and environmental justice in the American West. While she grew up in rural, remote northern Minnesota, she fell in love with the West while working in social services policy and programming in Telluride, CO. She has also coached Nordic skiing, served as an AmeriCorps VISTA, and guided backcountry canoe and backpacking trips. She holds a BA in geology from Carleton College. In her free time, Mara enjoys backcountry skiing, running rivers, rock climbing, and painting. See what Mara has been up to. | Blog