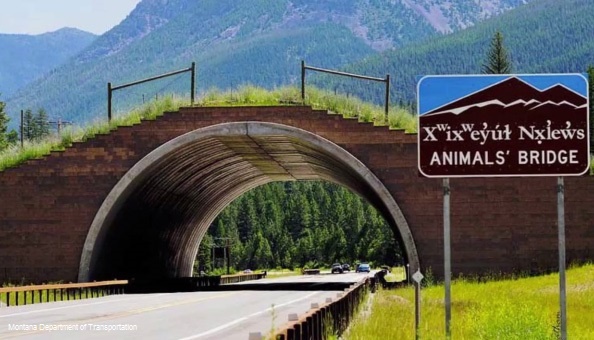

Driving north of Missoula through the Flathead Reservation, vehicles on US Highway 93 pass under a semi-circle arch of a vegetated overpass. Built to facilitate wildlife movement across the busy road, the overpass is a visible reminder that motorists are not the only individuals moving across the landscape. What motorists may not see as they continue north from Evaro, through Ravali, and past the Bison Range (previously the National Bison Range), are underpasses that facilitate wildlife movement underneath the highway, sections of wildlife exclusion fencing flanking the road corridor, and wildlife jump-outs. In addition to the overpass, culverts, bridges, and underpasses (38 in total) act as valuable conduits for movement underneath the road. Sections of wildlife exclusion fences keep large mammals off the road, away from traffic (wildlife-vehicle collisions are most reliably reduced when fence sections are greater than 5 km long [1]) all while aiding in funneling wildlife towards the crossing structures. And for individuals that get stuck inside the exclusion fences, the wildlife jump-outs allow for one-way movement out of the road corridor and back outside the exclusion fence. Together these engineered interventions allow species like white-tail deer (Odocoileus virginianus), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), black bears (Ursus americanus), coyotes (Canis latrans), raccoons (Procyon lotor), bobcats (Lynx rufus) amongst others to safely cross the highway. In Montana, across the US, and globally, wildlife crossing structures are becoming an increasingly popular tool employed to mitigate the road barrier effect on wildlife, and promote human-wildlife coexistence.

The presence and number of crossing structures along highway 93 in the Flathead Reservation is no coincidence. In the early 2000s, when a proposal was put forward to widen the highway, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) pushed for a “context-sensitive design” that included the wildlife crossing structures. “Protecting cultural, aesthetic, recreational, and natural resources located along the highway corridor and communicating the respect and value commonly held for these resources pursuant to traditional ways of the Tribes” was a guiding philosophy for the highway’s redesign. The negative and long-felt impacts that highways can exert on communities and ecosystems are well documented. With leadership and agency over their land, the CSKT pushed for a departure from business-as-usual road reconstruction to instead showcase opportunities for coexistence-based design by designating that “the road is a visitor and that it should respond to and be respectful of the land and the Spirit of Place”. Ultimately, the reconstruction of the 90.6 km-stretch of roadway resulted in a number of innovative design elements and one of the densest collections of wildlife crossing structures in the world.

Wildlife overpass spans US highway 93 in Montana. One of numerous engineered interventions included when the highway was widened in the early 2000s on request by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes to mitigate the road’s impact on landscape and near-by communities. Photo credit: Montana Department of transportation.

There are a number of ecological, economic, and social benefits associated with including wildlife crossing structures in the design or redesign of road corridors. Wildlife-vehicle collisions cause considerable loss of life (human and wildlife), injury, and cost Americans nearly $8 billion every year [2]. Wildlife exclusion fences alone would minimize these collisions, however, fencing without associated crossings would threaten the long-term viability of local wildlife populations by making already impermeable road corridors nearly impervious to wildlife movement. As a result, crossing structures are regularly coupled with fencing and placed where highways bisect important habitat, at sites where wildlife frequently cross the road, and areas known to have high incidences of wildlife-vehicle collisions. Larger structures like culvert underpasses and overpasses are often designed for larger mammals that pose the greatest threat to motorists. These larger structures can also benefit a range of non-target species including invertebrates, amphibians, medium-sized mammals, and reptiles. Though in many cases small-bodied species are more than just co-beneficiaries, projects often include structures and mitigation measures specifically targeting smaller species especially if the species are threatened or of high conversation value.

Crossing structures can never fully restore habitat connectivity to pre-road construction levels, however they can increase the permeability of the road corridor to wildlife movement. And in doing so, structures improve the long-term viability of wildlife populations impacted by the road. For local wildlife that are comfortable approaching the road corridor, crossing structures allow individuals to safely access habitat on either side of the road, populations to exchange genetic information, and select ecosystem dynamics to play out across the road rather than fragmented on either side. Additionally, strategically placing structures where roads intersect historic wildlife migration routes can maintain the ecological integrity of large landscapes and benefit populations like pronghorn or mule deer whose seasonal long-distance movements are threatened by roads. Site and species specificity are key when it comes to designing crossing structures and the dimensions, placement, and features of a specific structure are often determined by the goals of the project and the needs of the target species.

Culvert underpass offers wildlife that are willing to approach the road corridor a passage under highway 93 north.

In recent years, research illuminating the benefits of crossing structures has grown, fueling greater interest in structures themselves and the study of their role as elements in the landscape. As more structures are built and begin to age, researchers and managers are able to ask questions about how wildlife use of structures changes over a structure’s lifetime. Post-construction monitoring for wildlife movement is a common practice amongst wildlife crossing structure projects but rarely does funding support monitoring beyond 5 years. Studies find that once a structure is in-place, wildlife-use increases for a time before stabilizing [3][4]. Though it is reasonably assumed that the frequency of wildlife crossing increases and then plateaus over time, any changes in wildlife specie’s relationships to structures or use-behavior beyond the initial monitoring window are poorly documented. A study that compiled 121 major crossing structure connectivity investigations found that monitoring lasted on average less than 2 years [5]. Given that crossing structures can be in the landscape for more than 75 years, it is important to establish an understanding now of how structures perform over their full lifetime. With an improved understanding of how wildlife interact with and use structures over time, future projects will be able to better set targets for wildlife-use and even set goals for long-term connectivity improvements.

Camera trap captures a back bear (Ursus americanus) utilizing a culvert underpass to cross US highway 93.

Whenever I drive under the US highway 93 wildlife overpass on my way to the culverts underpasses that make up my study, I’m reminded of all the advances in the field of road ecology and crossing structure design as well as the leadership of the CSKT that led to the inclusion of wildlife crossing structure in the redesign of highway 93. I grew up next to the oldest wildlife overpasses in the country, and since their construction in the 1980s, the field of road ecology and wildlife crossing structures design have improved immensely thanks to a continued effort to research and improve crossing structures. The structures along US highway 93 have been the subject of a number of studies since their construction and in-turn, have led to improvements in our understanding of how structures and associated fencing function to mitigate the road barrier effect and minimize wildlife vehicle collisions. With my work this summer, I’m looking forward to adding to the growing research that will support future projects to continue to improve crossing structure design and increase the permeability of road corridors to wildlife movement. As attention is increasingly focused on mitigating the impacts humans exert on our environment, wildlife crossing structures offer opportunity and hope for human-wildlife coexistence.

References

[1] Huijser MP, Camel-Means W, Fairbank ER, Purdum JP, Allen TDH, Hardy AR, Graham J, Begley JS, Basting P. 2016. US 93 North Post-Construction Wildlife-Vehicle Collision and WildlifeCrossing Monitoring on the Flathead Indian Reservation between Evaro and Polson, Montana Final Report:159.

[2] Huijser MP, McGowen P, Fuller J, Hardy A, Kociolek A, Clevenger AP, Smith D, and Ament R. 2008. Wildlife-vehicle collision reduction study. Report to Congress. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Washington D.C., USA 232 pp. Available from: http://www.tfhrc.gov/safety/pubs/08034/index.htm

[3]Clevenger AP, Waltho N. 2003. Long-term, year-round monitoring of wildlife crossing structures and the importance of temporal and spatial variability in performance studies. Available from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3g69z4mn.

[4]Gagnon JW, Dodd NL, Ogren KS, Schweinsburg RE. 2011. Factors associated with use of wildlife underpasses and importance of long-term monitoring. The Journal of Wildlife Management 75:1477–1487.

[5]Van der Ree, R., E. A. van der Grift, N. Gulle, K. Holland, C. Mata and F. Suarez. 2007. Overcoming the barrier effect of roads – how effective are mitigation strategies? An international review of the use and effectiveness of underpasses and overpasses designed to increase the permeability of roads for wildlife. In: C. L. Irwin, D. Nelson and K. P. McDermott (eds.). Proceedings of the International Conference on Ecology and Transportation: 423–431. Center for Transportation and the Environment, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC.

Luca Guadagno, Western Resource Fellow | Luca is a Master of Environmental Science candidate at the Yale School of the Environment interested in the connections between nature based climate solutions, landscape-level conservation, and community-driven land stewardship. At YSE, he works on research and stakeholder engagement related to tree planting and forest management for multiple benefits, including for carbon drawdown, income generation, and ecosystem services. Before coming to YSE, Luca worked on human-wildlife coexistence research in Kenya and worked as an environmental educator. He received his B.S. in Biology and Environmental Science from Tufts University. See what Luca has been up to.| Blog