In the San Luis Valley, there are no shortage of views. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains rise like a wall on the east side of the valley and the San Juan Mountains usher in clouds from the west. The headwaters of the Rio Grande, the river snakes through the valley like a ribbon of green presenting a stark contrast with the native shrublands known as chico brush. However, these abundant views fail to reveal the valley’s most pressing natural resource concern–an aquifer that has been in steep decline for the last two decades.

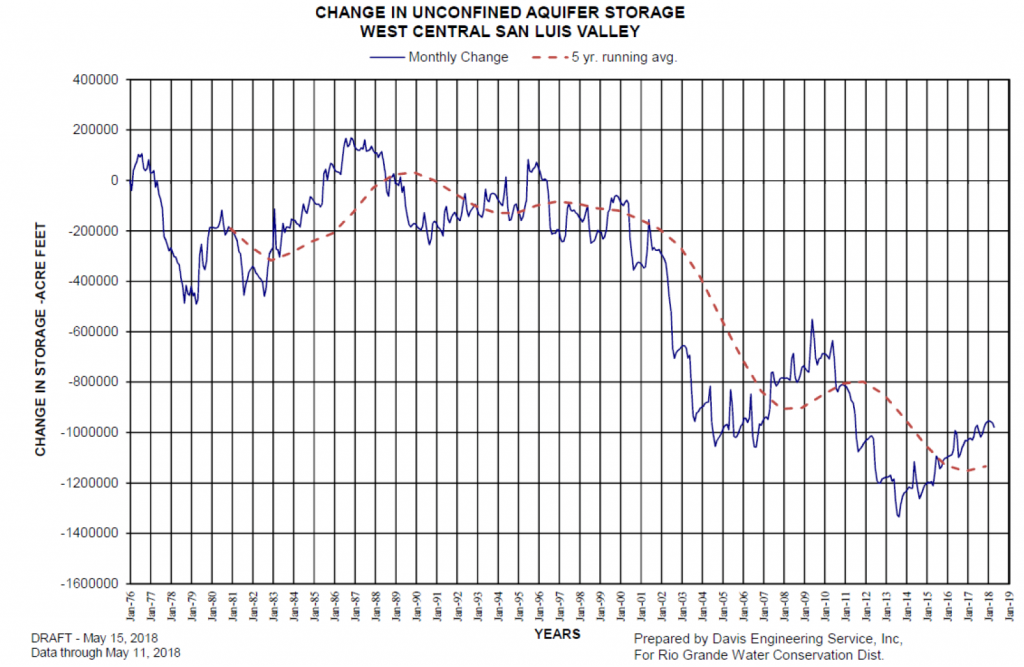

The San Luis Valley has two major aquifers, the confined and unconfined. This graph shows the decline in storage of the unconfined aquifer which exists in the first 100 feet below the surface. The confined aquifer, which exists at a deeper level has experienced a similar decline in recent years.

The size of Connecticut, the valley is one of the largest alpine valleys in the world, with an average elevation over 7500 feet. The landscape is heavily dependent on both winter snowpack from surrounding mountain ranges and the summer monsoon. This year, 2018, has already proven to be one of the three lowest runoff years on the Rio Grande in the history of scientific record. Comparisons between the record drought of 2002 were common until the monsoon arrived in the recent weeks, nearly a month later than it did in 2017.

In a year like this, where surface water is nearly nonexistent, farmers and ranchers turn to groundwater wells as they fall out of priority on the Rio Grande. That the river was fully appropriated in 1900 does not help the situation. Among natural resource managers there is a valley-wide acceptance that the river is seriously over-appropriated. Elsewhere in the West, this over-appropriation of surface water would result in a dry river and likely the retirement of agricultural lands tied to more junior water rights that were frequently out of priority on the river. In the San Luis Valley, the burden of this over-appropriation has been shifted to the aquifer as they turn to groundwater in dry years.

The Rio Grande Canal, relied on for surface water by the valley’s agricultural producers, has been dry since June.

I’ve been working with the Rio Grande Headwaters Land Trust (RiGHT) to help them develop a new conservation plan for the organization. After a successful initiative to conserve 25,000 acres over the last ten years, the land trust is interested in expanding its impact in the valley, while continuing their land conservation success. To develop the plan I have been meeting with natural resource managers and community members to better understand the state of natural resource issues in the valley, the role that RiGHT could play in the future, and how an actual plan might be implemented. Perspectives have been diverse, but the resounding concern has been for the sustainability of the aquifer.

The Rio Grande winds through the town of Del Norte, Colorado. Photo by Brendan Boepple, with assistance from Lighthawk.

Traditional agricultural conservation easements, the main tool for rural land trusts, have tied water to conserved lands. The practice was done to both ensure the long-term viability of a property’s agricultural production, but also to prevent transfer to Colorado’s growing Front Range cities. As the valley considers a more flexible water management regime to continue agricultural production while meeting aquifer sustainability, conservation easements can be seen as tying up water and reducing the amount available to meet valley-wide goals. The reality is that existing easement projects have ensured a healthy riparian corridor for the future. However, as RiGHT considers an expanded role moving forward, their easements may well need to aid in aquifer sustainability. Whether this means short term leases for aquifer recharge, split season irrigation that allows for instream flows later in the summer, or long-term leases that meet municipal needs to augment groundwater use, the valley’s water management will undoubtedly look vastly different than the past. How RiGHT finds a balance between land conservation and aquifer sustainability will be a major focus of the organization’s new conservation plan.